Following the Brexit referendum last year, when social media was groaning with opinions from those on both sides of the argument, an acquaintance of mine posted an innocent-sounding question on Facebook: why doesn’t the EU have a single, unified minimum wage? As most people attributed the referendum result to concerns over unchecked immigration to the UK from other parts of the EU, he thought this would solve many of the problems perceived to be caused by freedom of movement.

I can only speculate on the reasons behind his thinking. Perhaps he thought certain foreign workers, used to lower wages in their home country, could be paid less than their British equivalents while working in the UK, making them more attractive to employers there. This isn’t (or shouldn’t be) true; the UK minimum wage legislation applies to all employees regardless of nationality. Moreover, companies based in the EU who send employees to work in another member state need to be aware of the Posted Workers Directive (96/71/EC) which stipulates that posted workers are protected by the employment laws of the member state in which they work. This includes minimum wage regulations. (Directive 96/71/EC was recently complemented by Directive 67/2014/EU which updates some of the provisions of the original directive, in particular regarding enforcement. The deadline for transposing the new Directive was 18 June 2016.)

In other words, anyone working for less than the minimum wage is doing so illegally. Having the EU set the minimum wage instead of national governments won’t solve the problem of unscrupulous employers ignoring their legal obligations, unfortunately.

It’s more likely that he thought low-paid foreign workers would be less likely to relocate if the wage they would receive in the UK or elsewhere was the same as they would receive at home. Perhaps so, but there are many reasons why implementing a single minimum wage across the EU is easier said than done.

How would the rate be set?

Twenty-two of the 28 EU member states have a statutory minimum wage set by the government at a national level. The remaining six set minimum wages using Collective Bargaining Agreements negotiated between trade unions and employers, often at an industry sector level. This means that in these latter countries some workers may not be entitled to a minimum wage if their employment is not covered by such an agreement.

This is a simplification, however. Collective bargaining is also common in many of the countries that have a national minimum wage (Belgium and the Netherlands, for example), and the agreements negotiated there often improve upon the rates set by the government. A country where collective bargaining is common will therefore have multiple minimum wage rates in operation.

Further to this, some member states specify different minimum wages depending on the skill level of employees. Hungary has different rates for blue- and white-collar employees, for example, and the UK allows lower minimum wages for apprentices. It is also common to stipulate lower rates for younger individuals, as is the case in the Netherlands and elsewhere. Greece tiers its minimum wage rates according to age, marital status, length of experience and whether the employee is blue- or white-collar!

Resolving all these variations into a unified system for setting minimum wages across the EU would be complex to say the least, even if there was any appetite from the member states for doing so. Governments in those states with powerful trade unions that decide minimum wages through collective bargaining have clearly not felt the need to interfere with this process until now; they are unlikely to welcome intervention from Brussels.

What would the rate be?

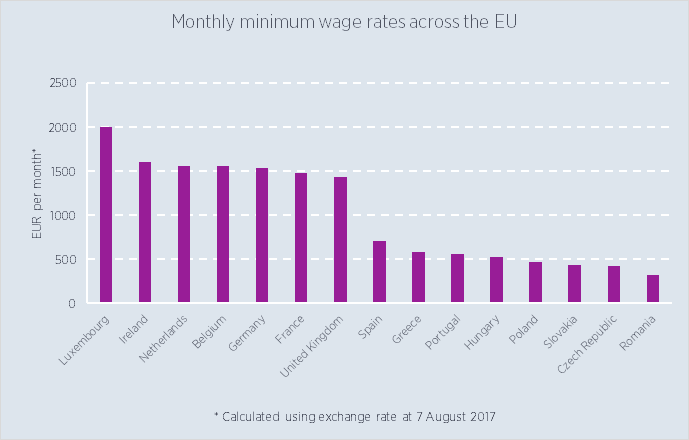

The chart below shows the monthly minimum wage in a selection of EU member states:

Assuming it was possible to align policies on setting the minimum wage across the EU, at what level should the pan-EU rate be set? The minimum wage in Luxembourg is currently over six times the minimum wage in Romania, two countries with very different levels of economic development. The countries at the high end of the scale cannot easily reduce their rates without opposition nationally, having already decided that their current rates are the minimum that should apply there. Instead, the countries at the low end of the scale would have to increase their rates considerably. Not only would this erode the competitive advantage these countries have by being able to offer cheap labour, which would likely receive opposition from employers, but there would be repercussions for their entire labour markets. The average wage paid to a junior manager in Romania, for example, is around EUR 1 300 per month – still less than the minimum wage in seven of the countries in the chart above.

(As an aside, this is why global mobility managers need to be aware of minimum wage legislation when assigning employees from countries with low local salary structures to countries with higher salaries. If a home-based approach is used to calculate the assignment salary, the result may not be sufficient to comply with minimum wage legislation or other minimum salary requirements (for obtaining certain visas, for example). A hybrid approach may be an option to provide a suitable safety net.)

So, Romania and other countries at the low end of the scale would not only have to raise their minimum wages but also wages paid to more senior staff to maintain appropriate relativities between job grades. Who is going to pay for these salary increases? Companies based in the countries affected would be unlikely to be able to cover the cost without assistance from their home government or other EU countries. The latter proposal is likely to be even less popular politically than allowing free migration from these countries. In addition, companies in affected countries might have to cut their workforces to absorb some of the increased cost which could, ironically, send more individuals in search of work elsewhere in the EU.

To be fair, while the idea of unifying the minimum wage across the EU has been put forward many times, at an official level few have suggested that absolutely the same rate should apply in each member state. Earlier this year European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said that all member states should have a minimum wage, but that each should set its own rate. In his 2016 report for the European Parliament on social dumping, French Socialist Guillaume Balas recommended that each state adopt a minimum wage of at least 60% of its median national wage. This should help to promote more even living standards across the EU but would still cost some countries a lot more to implement than others, most likely the lower-paying ones. Regardless, a disparity in absolute wage amounts between countries would remain, making some countries always seem a more attractive proposition than others.

Issues with exchange rates

A further issue with setting a minimum wage to apply across the whole EU is that not every country uses the same currency. There are ten different currencies used across the 28 member states. Assuming the minimum wage was set in euros, how would employers in countries outside the Eurozone know what amount to pay in their own country’s currency? Referencing the latest exchange rate every week or month would be unmanageable and result in unacceptable fluctuations in pay. A fixed exchange rate would need to be employed, perhaps reviewed annually.

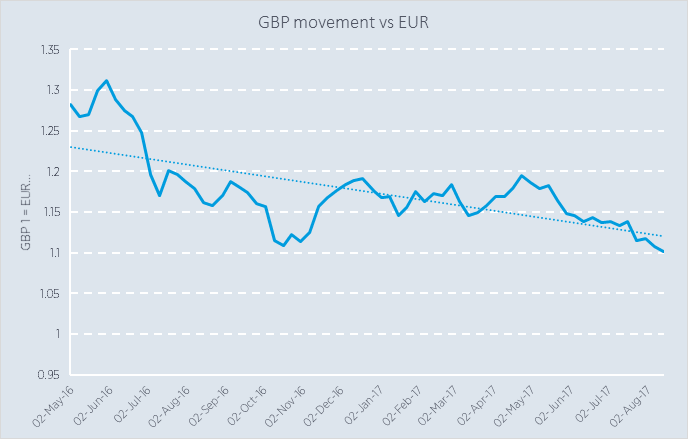

But any major movements in exchange rates over the course of the year could result in the “unified” minimum wage in one country being worth considerably more or less than that in another. Consider what has happened to the value of the British pound since the result of the Brexit referendum:

The National Living Wage (effectively the minimum wage for workers over 24) in the UK is GBP 7.50 per hour. On 20 June 2016, the day of the referendum, this would have been worth EUR 9.51. A year later it was worth EUR 8.58. This means that a minimum wage earner in the UK now earns around EUR 2 000 less per year than they did 12 months ago, due purely to the devaluation of the pound relative to the euro.

Assuming an annually-reviewed exchange rate was used to calculate the minimum wage in non-euro currencies, a repeat of this scenario would theoretically require the minimum wage in the UK to be reduced while the minimum wage in the Eurozone would stay the same. This might prove politically unacceptable, yet only adjusting the minimum wage for exchange rates when they move in the “right” direction would soon lead to disparities between countries that a unified minimum wage was supposed to solve. Perhaps some exchange rate fluctuations could be mitigated by inflation, but this only raises the question of how the minimum wage should be updated for inflation when both local price movements and wage policy differ across the member states. Belgium, for example, automatically updates its minimum wages according to national inflation each year.

Tax differences

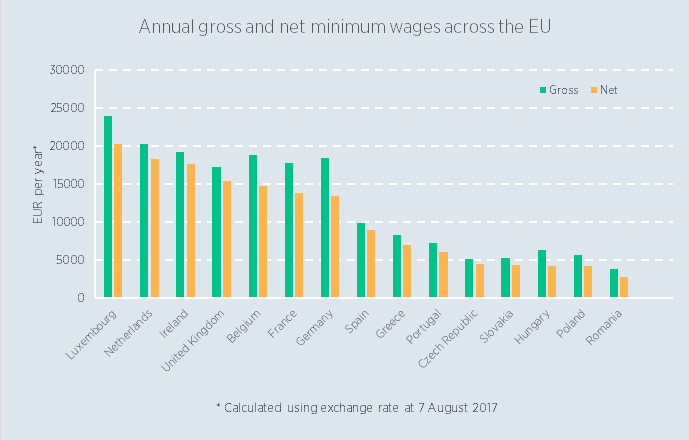

Even if all EU countries used the euro or exchange rates remained steady, the minimum wage would still have a different value in each country because wages are taxed differently in each member state. When the monthly minimum wages in the chart above are annualised and income tax and social security contributions deducted, the order of highest- to lowest-paying countries changes (calculations assume a single taxpayer with no dependents paying into the local social security scheme):

When gross salaries are compared, the UK appears to offer only the seventh most generous minimum wage of the countries shown. However, when net salaries are compared, the UK moves up the ranking by three places to become the country with the fourth most generous minimum wage. It would never be possible to truly unify the minimum wage across the EU without unifying the tax system too; an even more daunting and unlikely prospect! Also note that when cost of living indices are applied to the net salaries to compare them in terms of relative buying power instead of gross or net, there can be further changes in the ranking. ECA’s National Salary Comparison white paper has more detail about calculating and comparing salaries in terms of buying power and the effects seen at different levels of seniority.

Conclusion

The answer to the question of why the EU doesn’t have a unified minimum wage is long and complex. While it might seem desirable in terms of promoting social equality between member states, differences in economies, pay structures, currencies and tax law mean that a truly unified minimum wage would be almost impossible to achieve. It would also require the harmonisation of the many different approaches to wage-setting in operation across the EU, which is unlikely to receive universal support. The countries that don’t have a statutory national minimum wage are least likely to need one because employees there are generally well protected by agreements negotiated through various well-established models of partnership between trade unions and employer organisations.

A unified minimum wage may not be the most effective solution to social dumping in any case. A recent study for the European Commission found that stakeholders across the member states generally agreed that issues arising around paying the correct minimum wage for posted workers were due to poor enforcement, lack of information and certain parties finding creative ways to circumvent the rules. The 2014 update to the Posted Workers Directive mentioned earlier was intended to address such issues, and further revisions are under discussion. If these changes prove effective, the question of why there isn’t a unified minimum wage may no longer arise at all.

FIND OUT MORE

ECA’s Labour Law Reports are available as part of a data subscription and contain essential information to help you stay compliant. Each report provides overviews of statutory terms and conditions of employment (including minimum wage regulations), contract termination and industrial relations.

The Salary Trends Survey 2017 is now open! Take part before 22 September to receive a free report about actual and predicted salary increases for locally employed staff for over 70 countries.

Our National Salary Comparison white paper is a unique guide to how differences in local pay levels, tax and cost of living between countries affect the mobility management options available to employers. It is available to download free from our website. Subscribers to ECA data also have access to an interactive tool based on this report, comparing local salaries in 57 countries.

Please contact us to speak to a member of our team directly.