In the first instalment of this series, we wrote about trends in short-term assignments and how to structure packages.

In this article, we will review the basic principles relating to short-term international assignments, which can help to avoid some common mistakes and encourage best practices and proper compliance on the part of the employer. We will also bust a few myths – 183 days and the perception that short-term assignments are always less costly than a long-term assignment.

Short-term assignments may appear to make good business sense. The company does not have to spend considerable sums of money relocating a family, which in turn means less disruption to the family, and there’s no tax to pay in the host country if the assignment is less than 183 days. So, a win-win situation for both employer and employee. But things are never that simple and short-term assignments have their own set of peculiarities that make them as challenging and potentially as complicated as long-term assignments.

Tax considerations

183 days myth

Many companies are lulled into a false sense of security that as long as an employee is sent to work in another country for less than the magic 183 days, they think the employee will be exempt from that country’s tax. Well, that is simply not the case. There are many other factors besides days in this analysis. And in fact, some countries have a lower day threshold to determine if an individual is liable for taxes.

When residents of one country undertake short-term projects in another country, tax treaties frequently govern where and how the individuals are taxed. The OECD model tax treaty provides rules for the treatment of employment income for cross-border assignments under the clause ‘Dependent Personal Services’. Companies have grown to rely on the use of Article 15 of the OECD model to gain an exemption from income tax in the host country if three conditions are met:

-

The employee has not spent more than 183 days in the host country;

-

The salary is not borne by a permanent establishment of the employer in the country of assignment; and

-

The salary is paid by an employer, or on behalf of an employer, who is not resident in the state of assignment.

The basic principle of Article 15 of the OECD model sounds rather straightforward. If all three conditions are met, the right of taxation stays with the country of residence of the employee, and consequently the host country does not have the right to tax any employment income for duties performed in its jurisdiction.

However, as new treaties are drawn up, the interpretation of Article 15 of the OECD model is becoming more expansive. The 183 days used to be most often measured within a calendar year, but there is a trend towards looking at 183 days within a rolling 12-month period. In addition, tax treaties based on the idea of a ‘formal employer’ are giving way in many countries to a concept called the ‘economic employer’. This latter point is an important change with significant consequences.

Economic employer concept

Under the conventional tax treaties, the OECD model uses a ‘formal employer’ concept. A ‘formal employer’ is the entity which has a formal legal relationship with the employee. Under a typical short-term assignment arrangement, the formal employer is usually the entity initiating the assignment, paying salary from the employee’s home country and charging costs to the host company.

An ‘economic employer’, by contrast, is most commonly interpreted to be the entity controlling the day-to-day activities of the employee and the one that receives the benefits of the employee’s work. The move towards 'economic employer’ has come about because of the growing number of internationally mobile workers going from one country to another on temporary assignments with no fixed residence.

The economic employer concept typically comes into play on cross-border assignments when the taxing authorities of the host country decide that the host entity is the economic beneficiary of the employee’s efforts and should therefore bear the tax liability. This means that even if the employee has a formal legal relationship with the home country, the host country entity that is receiving the benefit could be construed to be the economic employer and, therefore, Article 15 of the OECD model would not be applicable to exempt the income from tax in the host country. The two factors creating an economic employer are:

-

the charging of costs; and

-

who controls the individual’s activities.

Article 15 of the OECD model does not use the term ‘economic employer’; hence the decision lies with the respective countries if and in what way they apply an ‘economic employer’ approach. Some countries give equal weight to both conditions; others consider that economic employment takes place if a single condition is met, although the charging of costs is no longer considered as significant as it once was and is rarely if ever an exclusive factor. The most important factor is who is controlling the employee’s activities.

To understand how this new concept is being applied in practical terms, let’s look at an example.

A German national on a four-month, short-term assignment in the Netherlands would typically be paid by his employer in Germany and remain a tax resident there. Because the Netherlands has adopted the economic employer approach in interpreting the term employer, the employee could be taxable from their first day in the Netherlands if the individual is under the supervision, direction and control of the host entity. Physical payment by the home country entity may suggest that the employee remains an employee of the home country entity but, because the actual work is performed under the direction of the host country entity, the individual is determined to be ‘in the service’ of the host country entity. Income taxes on the assignee’s base pay and other assignment-related income are therefore due in the Netherlands in addition to Germany.

Some countries do not apply an economic employer approach. As a result, in principle only the formal employer is decisive. Even a recharge between the home and host country entities does not lead to a different result, so that Article 15 of the OECD model may be applied in such cases.

Immigration considerations

Given the fast-moving nature of short-term assignments, processing times for immigration compliance regulations can sometimes be longer than the actual need for the assignee to be in the host country. Business visas can be quite straightforward to acquire and they can be issued quickly by the consulate or embassy of the host country. However, work permits are required for any activity exceeding a business visa that is deemed to be ‘productive work’ i.e. a business activity that creates revenue. This is an ambiguous term that can lead to frustrating scenarios when business activities are time-sensitive as processing times for work permits can often take four to six weeks. Business pressures may lead to managers circumventing strict limits on visas and avoiding lengthy bureaucratic processes by sending assignees into countries without the proper work authorisation. Thus, short-term assignees are more likely to be denied entry or detained at customs, creating emergencies for global mobility teams.

There should be no expectation that the employee can be sent to work in another country before a company decides on who will employ the individual. If an organisation already has an established entity in the host country, then the process of acquiring a business visa or work permit may be somewhat straightforward, even allowing for the bureaucracy of completing all the necessary paperwork. However, if a company does not have an established entity or subsidiary in the host country, then specialist advice must be sought well in advance to make sure the company complies with tax, immigration and employment laws. A ‘floating’ employee is an individual based in a country where the employer has no legal entity or physical presence. This may not be ideal in this situation as the host country may not permit a non-resident employer to act as a sponsor for immigration purposes. For example, in Brazil, to get a temporary visa, the employee must become employed by a Brazilian entity and enter into a Brazilian employment contract. In this instance, the company will need to have an established entity or subsidiary within the host country before the employee can be sent on assignment.

Cheaper and less administration myth

Short-term assignments are popular because they allow companies to transfer skill sets quickly and easily and are generally perceived to be more cost-effective than long-term assignments. These types of assignments also offer companies a possible solution to work/life balance.

However, there is a misapprehension that because of their duration, short-term assignments are cheaper or encounter fewer family-related problems. Just because an assignment is shorter does not mean it is easier or cheaper. In fact, a strong case could be made that short-term assignments are more fraught with potential pitfalls than traditional long-term assignments. In addition, many international companies have little idea of what they are spending on these alternatives to the traditional long-term assignment as comparatively few companies tend to run cost projections.

On the face of it, relocation costs for short-term assignments ought to be cheaper than a traditional long-term assignment. Employees undertaking short-term assignments are rarely accompanied by their partner and/or family. Hence, costs of physically relocating an entire family are mitigated along with children’s education costs, partner support allowances and costs of family-size accommodation. In addition, many employers will restrict the assignment length in an attempt to avoid any host country tax liabilities as well as to take advantage of any favourable home country tax treatment on assignment allowances and benefits.

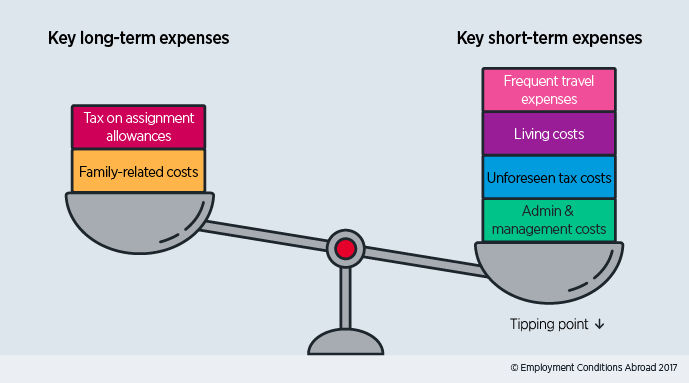

Will a short-term assignment always be less costly than a long-term assignment? Depending on the business objectives and the personal circumstances of an employee, there comes a tipping point at which an assignment undertaken on short-term provisions becomes more expensive to the company than a long-term assignment.

For example, travel costs mount up quickly especially if the assignee requests to travel back home more frequently than originally intended. Housing too can be a costly expense when the employee needs to be housed in hotels or serviced accommodation. If employees receive a per diem or untracked expense reimbursement, these can create costly liabilities and can add significantly to the management and administration of short-term assignments.

Short-term international assignments, as compared to a long-term assignment, do not always result in a lower tax and assignment cost to the company. Certain living expenses may sometimes be provided free of home country taxes. However, if the host country taxes these payments, and assuming the host country effective tax rate is equal to or higher than the home country tax rate, restricting the assignment duration may not yield the desired tax benefits.

Perhaps the greatest risks facing an employer are unplanned tax liabilities. Very often, managers will extend a short-term assignment contract for a few weeks or possibly a couple of months, not recognising the implications or giving thought to the tax issues. The assignee could inadvertently become subject to local income tax withholding and social security contributions, and the employer could also be obligated to pay their statutory share of social security. Under such situations the employee may face double taxation, especially where a tax treaty does not exist. Extending an assignment for only a matter of days could, in some countries, create a corporate tax liability as the employer may appear to have an office there (Permanent Establishment). It would be advisable for global mobility teams to consult with corporate tax advisers to determine that proper agreements are in place between the home and host entities to mitigate any PE exposure.

Family support considerations

While a structured short-term assignment may sound like a solution to help overcome barriers to mobility, such as dual career households and disruption to children’s education, the reality is that family separation can cause a lot of friction in the family. Split families can incur some financial loss because of an employee accepting a short-term unaccompanied assignment. As a result, a minority of companies consider offering different types of family assistance, such as home maintenance, child or elder care support. A few companies will provide allowances to compensate for an enforced family separation and permit the assignee to allocate costs to family expenses most important to their personal, family circumstances. Alternatively, some companies find that frequent home-leave allowances can be quite helpful.

In the next article, we will address how companies can achieve greater consistency when structuring short-term assignments.

FIND OUT MORE

Please contact us to speak to a member of our team directly.