Helping international companies manage expatriate pay in relation to relevant exchange rates is, of course, a core part of our service at ECA. But many clients also employ local nationals in their countries of operation and sometimes the distinctions between how the two types of employee can be affected by currency values become blurred.

Recently, for instance, among the concerns sparked by slumps in the Argentinian peso, the Sudanese pound and the Angolan kwanza, some companies were worried they might need to adjust not only foreign assignees’ salaries, but those of local employees too.

The measures they were considering included one-off payments; immediate uplifts to pay levels; shifting pay delivery into hard currencies; and increasing or introducing new benefits. Any or all of these might be sensible options for foreign assignees, although even then it would depend on factors such as local payroll laws, current pay-delivery currency splits, the timing of standard salary reviews etc. However, for local staff on local terms and conditions, paid in local currency, such measures are generally not recommended.

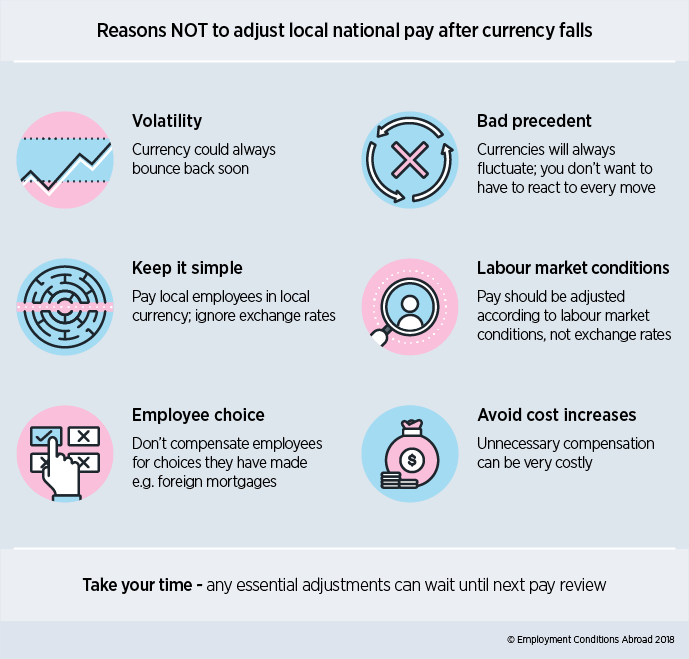

The first problem is a common one where currencies are concerned: volatility. Who’s to say the sharp fall in the currency you’re adjusting for won’t completely reverse in the next six months? If it did, could you ask your employees to give their extra payments back? And what precedent has now been set, given that currencies always fluctuate? Potentially a costly one.

Secondly, when local staff are paid solely in local currency, there is no need to consider any exchange rate; there is no other currency against which you need to measure the value of the one you’re paying in. So what are you trying to adjust for?

Indeed, the simplicity of paying entirely in local currency is why it is almost always the right policy for local staff. So, to shift pay delivery into hard currencies in response to a moving, but irrelevant, exchange rate would not only be illogical but also add significant complications which you could regret later on.

Assuming you are a local hire working in your own country (as the vast majority of us are), you wouldn’t expect to receive a pay increase just because your local currency decreased in value, even if it fell against lots of others. Devaluations don’t lift the cost of living directly, but rather indirectly through import price inflation (which tends to lag the exchange rate decline and could in the meantime be offset by other factors anyway). Your pay may need to be adjusted later to maintain your standard of living, but if so, your company will look at inflation rather than any exchange rate, and they would be wise to wait until annual review time in any case, or at least until things have settled down.

Furthermore, pay is generally adjusted according to local labour market and industry conditions, with usually just a passing reference to inflation, so unemployment rates and availability of relevant talent are better guides to reviewing pay than consumer price indices – and they are certainly more useful than exchange rates. Most companies need to stay competitive and keep costs down, so they’re unlikely to pay over the odds just because the local currency can now purchase fewer imported goods. The payee has, in many cases, the option to buy locally-produced, cheaper goods from now on instead.

Local nationals sometimes have commitments abroad, such as foreign mortgages, or schooling costs for children studying in other countries, and companies can be tempted to try to help such employees when the local currency has become comparatively devalued. However, in these situations, exposure to exchange rate fluctuations results from choices made by the employee and not the company, so there’s no reason why an employer should feel obliged to compensate. They may see gains from helping out with loans, perhaps for particularly valued personnel, but generally employees should be encouraged to manage these sorts of issues themselves.

Some staff are employed on so-called ‘local-plus’ terms, which generally means they receive pay according to local market rates, but also receive foreign-assignee-type benefits on top. Whether or not benefits need to be adjusted in the wake of a local currency collapse depends on how they are delivered. If the company pays providers directly then there’s no issue for the employee. If the worker receives an allowance to pay for benefits, then any adjustment will only be needed when and if the cost of the benefit rises, which is likely to lag the currency decline and can probably therefore wait until standard annual pay review time.

In conclusion, it is easy to be spooked by headlines about currencies plummeting, and expatriates often are, in some cases with a degree of justification. But for local nationals, usually the impact will be minimal, indirect and slow enough that waiting for the next pay review, when adequate compensation can be made if necessary, is almost always the right course of action. Incidentally, the same is generally true for foreign assignees too.

FIND OUT MORE

If your company has any global mobility needs, ECA is here to help.

Our team of experienced consultants is on hand to critique your existing policy documents or create them from scratch, so that the resulting policies are aligned with market practice and your company's business objectives whilst also being free from ambiguity and risk of misinterpretation from assignees and stakeholders.

Our National Salary Comparison white paper is a unique guide to how differences in local pay levels, tax and cost of living between countries affect the mobility management options available to employers. It is available to download free from our website. Subscribers to ECA data also have access to an interactive tool based on this report, comparing local salaries in across the world.

Please contact us to speak to a member of our team directly.