The great shift to remote working during the past two years is now firmly rooted and seemingly here to stay. Organisations across the world have adapted, and are still adapting, to widespread working from home, hybrid working and flexible working patterns – a dramatic shift made necessary by the COVID-19 pandemic, but one that has proven successful.

One version of remote working that’s been gaining traction and making headlines is international flexible working. As we found in our recently published Global Mobility Now Survey, approaches to this kind of remote working vary wildly. Some companies have adopted a ‘work from anywhere policy’ that allows employees to work in another country for up to 30 days – our survey found that one in four companies impose this time limit. At the other extreme, one in five companies would allow these working arrangements to continue indefinitely. Across the board, organisations report that approval for these kinds of moves hinges on the legal implications – i.e. the employee having the right to work, and the organisation having an entity, in the country in question – as well as business needs. But regardless of the parameters – in the context of the ‘Great Resignation’ and battle to attract and retain global talent, offering flexibility and prioritising the employee experience can be an effective way for employers to gain a competitive advantage. In some cases, it could also help companies to reduce their climate impact, if replacing regular cross-border commuting by car or air.

This said, there are some substantial challenges that come with international remote working. The best known and most discussed are compliance issues – with income tax, social security, permanent establishment risk and immigration rules all notoriously difficult to navigate. The question of remuneration, however, cannot be neglected. Pay for these international flexible workers is complex and difficult to get right, but essential to the success of these arrangements.

How should you pay?

If an employee requests to work from another country, your first instinct may be to make no changes to their compensation – if the move is initiated by the employee and is being facilitated by the company solely for the employee’s benefit, it may seem obvious that it is for the employee themselves to bear the consequences for their net pay. However, you are likely to find that doing nothing is not always best for the business. If the priority is retention of valuable talent, you may wish to actively ensure that the pay will be sufficient for the upkeep of the living standard that the employee was accustomed to in the home location.

Conversely, if an employee is hoping to save costs and enhance their pay – by moving to a location with a lower cost of living or lower tax burden – this might guarantee their satisfaction but present a problem with equity. For example, locally employed peers may begrudge their new colleague working in the same location as them while still on an overseas pay structure that compensates for higher tax and higher living costs in that country. From another perspective – perhaps the arrangement is meant to be temporary, and your concern is that a windfall from working in the employee’s chosen location will make it impossible to incentivise repatriation later on.

On the other hand, offering a local package as a matter of course isn’t necessarily the right answer either. If the employee is moving to a country with lower pay levels relative to the home country, at least at their seniority level, then this would make for an unattractive offer. Even if the local salary is higher at first glance, this can be deceptive. A higher gross does not necessarily make for a higher net salary – the employee may be moving somewhere with a significantly higher tax burden. And there is also the question of what living and housing costs mean for the salary in real terms.

This is where a net-to-net calculation comes in. You can compare the employee’s home salary with a local offer in net terms, to see if it’s a viable option. ECA’s Net-to-Net Calculator automates this process – you simply input the home and local gross salaries and the calculator deducts tax and social security accordingly. There is also an option to factor in cost of living and housing cost differentials to determine whether the local net salary is enough to maintain the living standard the employee is used to.

Let’s consider an example scenario. Your employee, currently living in the UK and employed under a local contract, wants to move to Guadalajara and continue working for the London entity remotely for a year. You have an office in Mexico but before benchmarking this employee to their peers in the country, you want to see if it’s feasible to pay them the same gross salary locally in Mexico as they were on in the UK. This employee is highly valued and you want to facilitate this move and keep them at the company, but you would prefer they eventually return to the UK to work in the London office in person.

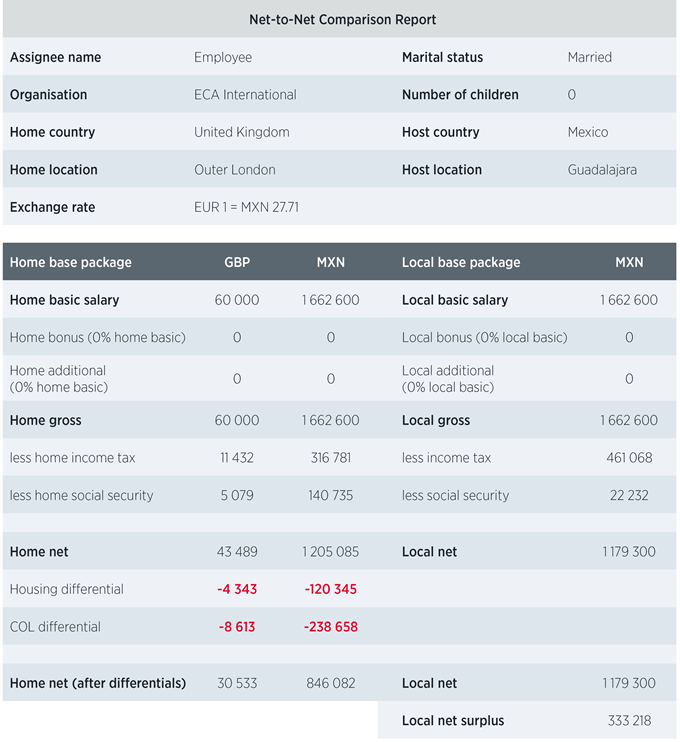

At first glance, looking at the net-to-net calculation below, we might expect that the employee would not accept the same gross salary of GBP 60 000, simply converted into Mexican pesos i.e. MXN 1 662 600. The tax and social security deduction is higher overall, resulting in a lower net salary in Mexico than in the UK. Maintaining the employee’s nominal home net salary would require a local gross salary of at least MXN 1 701 668, at increased cost to the business.

However, if we take cost of living and housing differentials into account when running the net-to-net calculation, the picture is altogether different (see below). Living and housing costs are lower in Guadalajara than in Outer London – so in order to have the same living standard, the employee only needs a net salary of MXN 846 082. If the home gross salary is maintained at the same level while the employee works from Guadalajara, their net salary in real terms, i.e. adjusted for purchasing power, will be higher than at home.

The calculation shows that paying the employee the same gross salary while working from Mexico protects (and improves!) their living standard and incentivises them to stay at the company. However, this doesn’t take equitable treatment into account; if the employee’s peers in Mexico at the same job grade are on lower salaries, this might present a problem. Another possible dilemma is that in a year’s time, the employee is likely to be loathe to return to the UK without a pay rise, having benefitted from cheaper living costs in Mexico and being used to a higher living standard. The Net-to-Net Calculator enables you to run limitless calculations to compare and explore every local offer under consideration to the home salary – so, depending on your priorities, the next step might be to benchmark against the net of a local salary in Mexico for the same job grade, or find a pay offer that balances protecting the employee’s living standard without triggering a huge rise in them.

Offering an international flexible remote working policy can potentially be a great way to retain and attract talent, but – among other obstacles – deciding how to pay international remote workers can clearly be a tricky balancing act and may need to be considered carefully on a case-by-case basis. Net-to-net comparisons are indispensable for testing out the viability of each pay approach in each case, and with ECA’s Net-to-Net Calculator each scenario can be run in just a couple of minutes.

FIND OUT MORE

The Net-to-Net Calculator can be added to ECA subscriptions for access within MyECA, and activated for authorised users in a matter of hours. If you only have an intermittent need, net-to-net calculations are also available to both existing ECA subscribers and non-subscribers through our Client Services and Consultancy services. They can also be incorporated into ECAEnterprise, ECA's Assignment Management System.

If you haven't read this series already, you may be interested in our previous blog posts on international remote working listed here:

Please contact us to speak to a member of our team directly.